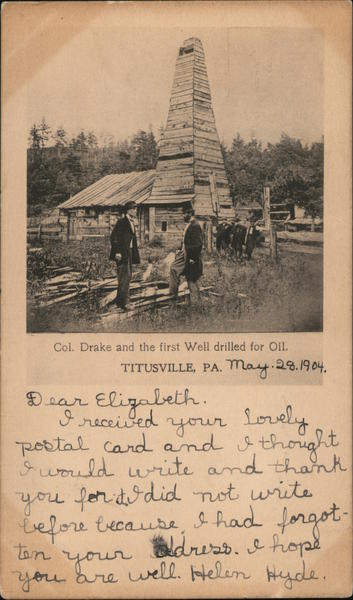

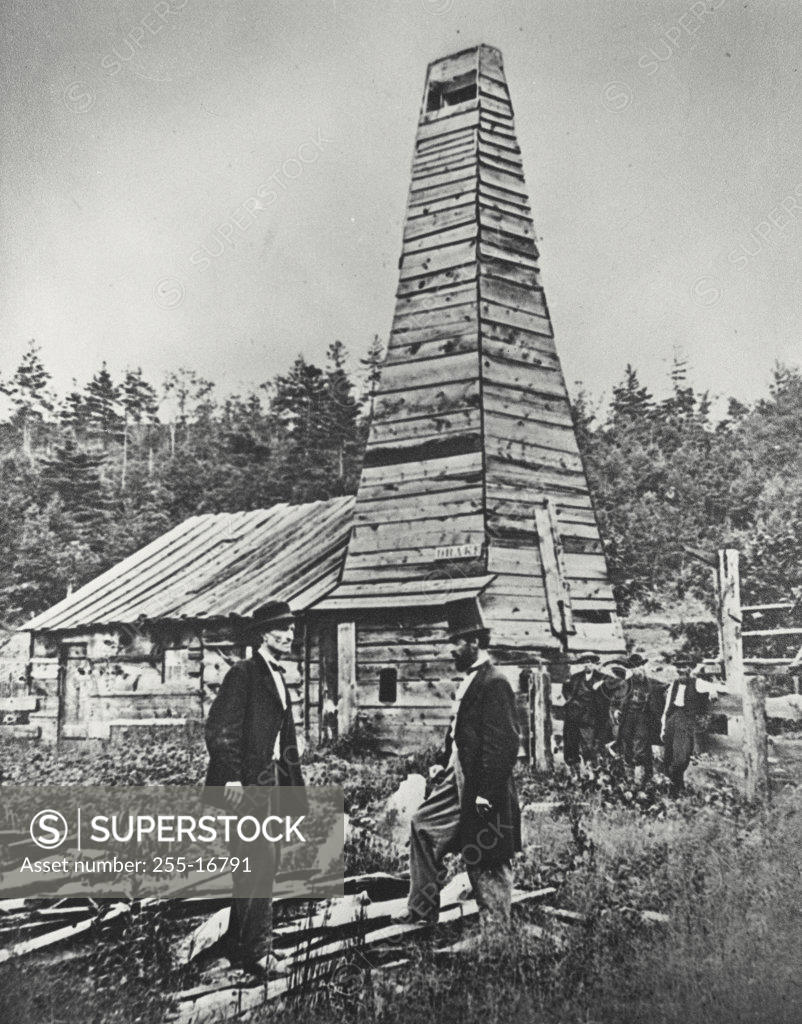

When my field trip class arrived at the Drake’s Well Museum I remember seeing an odd looking wooden building with an awkward chimney-like structure on one side. While Edwin Drake lived a hard life even after his discovery, he is still considered the father of the modern petroleum practices and industry³. While Drake’s Well was not the most productive, or largest oil well, the Titusville site is globally significant because it kick-started the petroleum drilling revolution that eventually changed global economies and environments. Through experimentation and innovation, on August 27, 1859, Drake struck oil when his drill reached a depth of 69.5 feet. Productive oil drilling required new techniques, and one of Drake’s most important innovations was the “drive pipe,” sections of cast iron pipe driven into the shaft to protect the drill bit from water and cave-ins. Although this method works for producing salt, it was far less efficient for producing oil. Salt wells used water to dissolve salt source rock, and then carry the resulting brine through piping to the surface where it would be evaporated to leave salt as a solid residue. However, the purpose of Drake’s Well was to produce oil for refining into kerosene for lamps, and thereby provide an alternative to the whale oil then used to illuminate homes and workplaces. Ointments, antihistamines, antibacterials, cough syrups, and even aspirin are created from chemical reactions created from petrochemicals². Even today, chemicals made from the refining of petroleum are responsible for many of our modern medicines. In small doses, oil was used to treat respiratory diseases, epilepsy, scabies, and other ailments¹. In the early 1800s oil was an unwanted by-product from salt wells (wells used to mine salt), and before that, a traditional medicine.

These Indigenous people, who were removed from their native lands in the 1700s, 1800s, and 1900s, did not benefit from the Seneca Oil Company. The company took the name from the Seneca Nation, one of the original Five Nations of the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy, who had long made use of the resource Drake sought by skimming naturally-occurring slicks of petroleum, or unrefined oil, from the surface of local waters. Drake who in 1859 struck oil outside of Titusville for the Seneca Oil Company. The site is named after the well’s driller, Edwin L. Our field trip took us to Titusville, Pennsylvania to visit Drake’s Well, the first commercial oil well in the United States. When I was older, I pursued a degree in geology and began to understand more about my local community. But I was too young to grasp how this tired little town’s geology had changed the global economy and course of human history. I remember thinking, even at that young age, that the area looked worn and just, well, tired. I had family in the Titusville and Oil City area, so it was a familiar route to take with my parents.

I remember seeing the familiar road signs and buildings as our bus gassed along the back roads. Around 4th grade, I remember taking a field trip to Titusville, Pennsylvania. I went to a small school with about 300 kids in K-6th grade. I grew up near Venango and Crawford County and had a rural childhood. I am a fries-on-salad, haluski dinner, dairy farm heritage kind of Western Pennsylvanian.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)